President Trump has accepted the Nobel Peace Prize that was awarded to Venezuela’s opposition leader, María Corina Machado. Unlike Machado, however, he does not accept the central lessons that can be gleaned from five decades of Venezuelan misrule. There are three.

Lesson 1: Past prosperity is no guarantee of future prosperity.

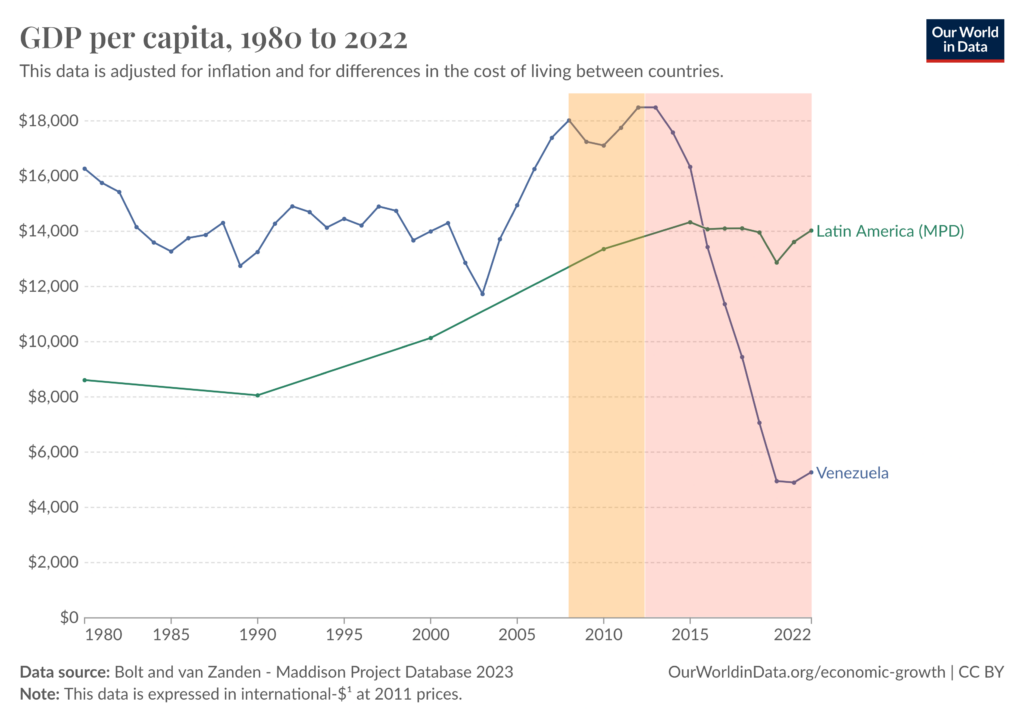

In 1970, Venezuela was the wealthiest country in Latin America. Sitting atop the world’s largest proven oil reserve, it churned out more than 3.5 million barrels of oil a day. Using GDP per person as a metric, its citizens earned 2.7 times as much as the rest of Latin America — about the same as the average Finnish, Japanese, and Italian citizen.

This prosperity bought Venezuelans better health, longer life, and more creature comforts — especially fancy foreign cars that poured into the country as oil poured out. And it wasn’t just the wealthy that benefited. Venezuela’s poverty rate was about a third of what it was in the rest of Latin America.

The zenith was around 1977. Thanks to the global oil crisis of a few years earlier, crude prices had quadrupled. Amidst the boom, President Carlos Andrés Pérez made the fateful decision to nationalize the country’s oil industry, hoping to use its wealth to fund economic development and poverty relief. Instead, by combining public and private interests, the decision proved a boon for corruption, eventually turning the country into a petrostate.

Almost immediately, incomes began to fall. By 1999, average Venezuelans were earning less than 90 percent of what they had three decades earlier. But the worst was yet to come.

Which brings us to the second lesson.

Lesson 2: Policy matters.

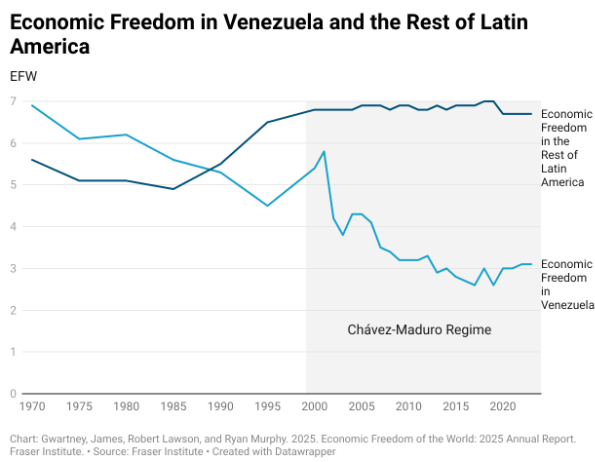

Oil was not the only explanation for Venezuela’s 1970s prosperity. The government spent and taxed modestly. It left most industry in private hands. Inflation was low. And international trade was almost entirely free of tariffs and regulatory barriers to trade.

In 1970, Venezuela scored a little less than 7 on the Fraser Institute’s 10-point Economic Freedom of the World index, making it the 13th most economically free country in the world, just ahead of Japan.

But as the rest of the world liberalized in the 1980s and 1990s, Venezuela went in the opposite direction. The government ramped up transfers and subsidies and began to acquire more assets. Property rights grew less secure. Inflation reached 26 percent in 1980 and over 50 percent in 1995. By 2000, Venezuela had slipped to 116th in economic freedom.

In 1999, as the economy faltered, a frustrated electorate turned to an outsider, Hugo Chávez. Chávez had risen to fame seven years earlier when he led an unsuccessful coup d’état against the democratically elected government (ironically led by Andrés Pérez, who had returned as president in 1989).

Though left-of-center, he did not begin as a radical. Instead, he positioned himself as a populist reformer who could steer a “Third Way” between socialism and capitalism. But he grew more radical after a failed coup attempt against him in 2002. By 2005 he had fully embraced the socialist label, recasting his movement as “Socialism of the 21st Century.”

It wasn’t just branding. He nearly doubled transfers and subsidies and more than doubled government investment. He tightened control over the government-owned oil company and nationalized other industries, including steel, iron, mining, cement, farming, food distribution, grocery chains, hotels, telecommunications, and banking. The government stopped respecting and protecting private property. Annual inflation bounced around from 20 to 60 per cent. At the time of his death in 2013, Venezuela’s overall economic freedom was close to 3 on the 10-point scale, making it the least economically free country in the world.

But as the government took, nature gave. The country’s massive Orinoco Oil Belt continued to churn out about 2.5 million barrels of oil every day. As a result, GDP per person recovered.

Many Western observers, from Senator Bernie Sanders to director Oliver Stone, saw this as a sign that socialism works. But the reality is that Venezuela’s oil-fueled boom had only managed to bring incomes back to 1970s levels. Moreover, careful econometric analyses comparing Venezuela’s performance to that of other similarly situated countries, found that Venezuela consistently under-performed.

Chávez died in 2013, leaving the country in the hands of his Vice President, Nicolás Maduro. Maduro clung fast to Chávez’s policies, but as global oil prices plummeted, Socialism of the 21st Century began to look a lot like socialism in the 20th century: incomes collapsed, poverty exploded, and inflation became hyper (reaching over one million percent in 2018).

Maduro responded predictably, imposing price controls that produced massive shortages of household necessities. About a quarter of the population fled the country.

But the cost was not merely economic. Which brings us to the final lesson.

Lesson 3: Economic and Personal Freedom are Deeply Intertwined.

Socialism is typically imposed at the point of a gun. But notwithstanding his attempted 1992 coup, Chávez had come to power through free and mostly fair elections. This seems to have been one reason why Western observers were so taken in by the regime. Writing in her 2007 book, The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein claimed that Venezuelan “citizens had renewed their faith in the power of democracy to improve their lives.”

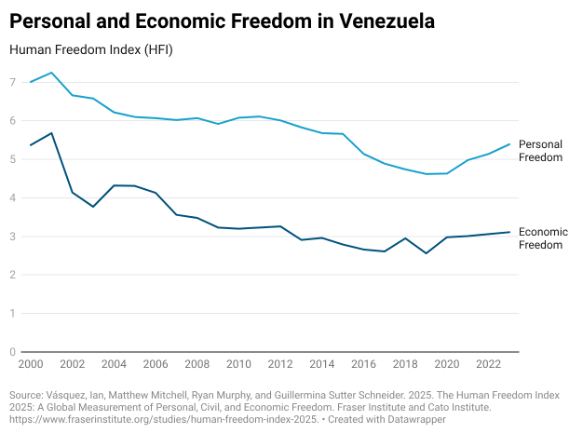

But if she had looked closer, she would have seen the early signs of Venezuela’s anti-democratic turn. The Human Freedom Index, co-published by the Fraser Institute and the Cato Institute, builds on the Economic Freedom of the World index by adding 7 additional areas of personal freedom. As the figure below shows, the regime cracked down on personal freedoms just as it limited economic freedoms. By the time Klein wrote her book, Venezuela had already severely restricted freedom of expression, freedom of religion, freedom of association, freedom of movement, and the rule of law.

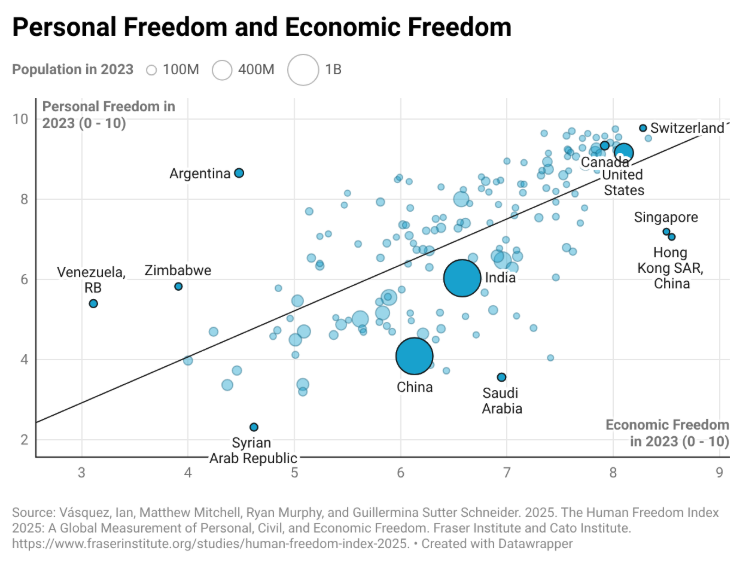

This, unfortunately, is common. As we see in the final figure, most regimes that restrict economic freedom also tend to restrict personal freedom. It is easy to imagine why. People value their economic liberties, so regimes that seek to severely repress these liberties often cling to power by suppressing dissent. And because socialist regimes own the means of production — including media production like radio, print, and TV outlets — they have a handy tool at their disposal for suppression.

What now?

As the Cato Institute’s Marcos Falcone recently explained, one Venezuelan who seems to have internalized these lessons is María Corina Machado. As a decades-long leader of the opposition, she has consistently championed both personal and economic liberty. She traces much of the country’s corruption, mismanagement, and stagnation to its 1976 nationalization of the oil industry.

And she is wildly popular. In the unified opposition primary of 2024, she ran on a platform of complete oil privatization and won 90 percent of the vote. Maduro refused to let her run in the general election, so she backed Edmundo González Urrutia and he is estimated to have won 70 percent of the vote. But Maduro refused to recognize the result and clung to power.

Now, apparently, President Trump is in charge. But like Maduro before him, Trump refuses to recognize the results of the last election. He claims that Machado lacks the “respect” and “support” to lead. Polls, meanwhile, indicate that she is favored by more than 70 percent of the country. While accepting her re-gifted Nobel Prize, Mr. Trump has decided to give the reins to Maduro’s Vice President, the socialist Delcy Rodriguez, calling her a “terrific person” and predicting a great Venezuelan renaissance.

As for privatization, Trump instead says “we’re going to keep the oil.” He claims that Rodriquez will be “turning over” up to 50 million barrels to the US, the proceeds of which will be “controlled by me, as President of the United States of America.”

Meanwhile, he is strong-arming US oil companies to invest in the country, telling them that if they want to recover their property that was seized by President Andrés Pérez in 1976, they’d better cooperate in rebuilding Venezuela’s infrastructure. For their part, the companies have been reluctant to do so, citing the country’s poor track record of protecting private property.

Like Andrés Pérez, Chávez, and Maduro, Trump seems to imagine that the right central plan will unlock the country’s vast oil wealth. But history teaches a different lesson.

0 Comments