In early 2021, a declining video game retailer unexpectedly became the epicenter of one of the most extraordinary episodes in modern financial history. GameStop saw its stock price surge from under twenty dollars to well over four hundred in a matter of days, propelled by an unusual combination of extreme short interest, coordinated retail buying, and feedback loops embedded in contemporary market structure. Hedge funds suffered dramatic losses, trading platforms restricted activity under operational strain, and Congress called hearings in rapid succession. What might otherwise have been a transient market dislocation quickly became a cultural and political event. The episode was soon framed as a populist revolt — small investors versus Wall Street, social media versus institutional finance, narrative triumphing over fundamentals.

Yet beneath the spectacle lay quieter and more enduring economic issues. The first is the massive impact of record levels of fiscal and monetary expansion during the pandemic. The other remains unresolved even today, years later. The GameStop episode was not merely a story about price volatility or market plumbing. It was a case study in what happens when capital markets intervene so forcefully that they separate a firm’s financial survival from its economic validation, disrupting the market’s normal process of error correction.

From an Austrian perspective, markets are not allocators of abstract “efficiency,” but discovery processes. Prices, profits, and losses transmit information about what consumers value and how scarce resources can best be employed. Losses are not pathologies; they are signals — evidence that entrepreneurial plans have failed to align production with consumer demand. When those signals are muted or overridden, discovery slows, and misallocation persists.

GameStop did not merely experience a temporary price spike. The short squeeze fundamentally altered the company’s financial condition. By issuing large quantities of equity at elevated prices, the firm raised billions of dollars, eliminated near-term bankruptcy risk, and transformed its balance sheet almost overnight. A business that appeared to be on a downward glide path suddenly possessed a war chest large enough to attempt reinvention. The market had not merely repriced GameStop; it had suspended the binding constraint that normally forces rapid learning.

That outcome raises a question that extends well beyond a single retailer: did the short squeeze save an ailing firm with unrealized entrepreneurial potential, or did it prevent the liquidation of a badly run business that had already failed its market test? The distinction is central to Austrian economics. Saving a viable firm can allow entrepreneurial recombination and reorganization. Preserving a failed one risks freezing capital and labor in lines of production that consumers have already rejected.

Economists often distinguish between financial survival and economic validation, though popular discussions frequently collapse the two. A firm survives when it has access to capital. It is validated when customers willingly pay prices that cover costs and generate sustainable cash flow. These conditions frequently coincide, but they need not. When they diverge, capital can keep a firm alive even as its business model remains unproven — or has already been disproven.

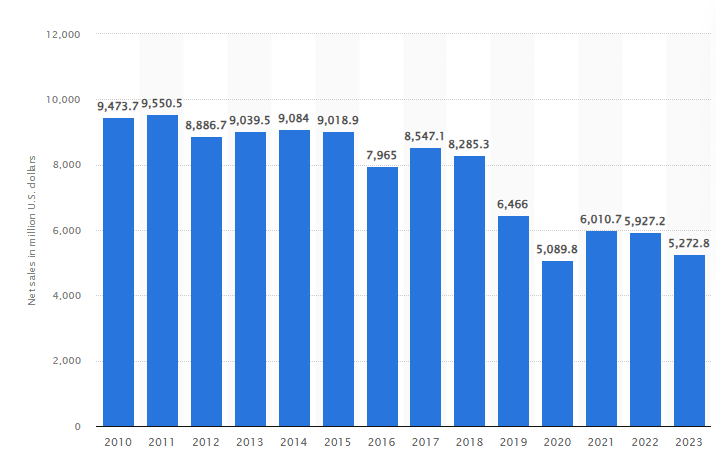

Before 2021, GameStop had largely lost that validation. Physical game sales were shrinking, margins were under pressure, and the steady shift toward digital distribution — through platforms owned by console manufacturers and publishers — was eroding the retailer’s role in the value chain. Losses were persistent rather than cyclical. By 2021, revenue had been in decline for over a decade, and in 2018 saw sales of its primary product, pre-owned and value goods, drop by 13 percent. The store footprint was oversized relative to demand. Cash flow was deteriorating. These were not temporary setbacks caused by a weak quarter or a singular shock; they reflected structural decline in the firm’s core business.

Net sales of GameStop worldwide from fiscal 2010 to fiscal 2023(in million US dollars)

Under ordinary market conditions, such a firm faces a reckoning. It restructures sharply, shrinks to its profitable core, or exits. From an Austrian standpoint, this is not “market cruelty” but knowledge transmission. Capital and labor are released from failed uses and redirected toward higher-valued ones. Liquidation is not the destruction of value; it is the recognition that value has already been destroyed and that further losses should be arrested.

The WallStreetBets-driven short squeeze disrupted that process. By allowing GameStop to raise equity at prices far above any reasonable estimate of near-term earning power, market discipline was suspended. The firm’s survival was no longer contingent on consumer choice. Capital substituted for cash flow, and the hard budget constraint that normally enforces entrepreneurial discipline softened dramatically. Losses became tolerable. Time was purchased.

From an Austrian perspective, this matters because constraints are not arbitrary. They are the mechanism through which markets force alignment between plans and reality. When those constraints are relaxed — whether by central banks, governments, or speculative capital surges — error correction gives way to error tolerance. The system continues to function, but it functions more slowly and less accurately.

To be clear, buying time is not inherently irrational. Capital markets sometimes fund loss-making firms when uncertainty is high and future payoffs are difficult to forecast. Optionality has value. But Austrian economics emphasizes that time without discovery is not neutral. The question is not whether GameStop gained time, but whether that time was used to generate genuine entrepreneurial learning.

Following the squeeze, the firm pursued a series of initiatives framed as transformations rather than incremental improvements. The most visible was the launch of an NFT marketplace in 2022, intended to position the company at the intersection of gaming, digital ownership, and online communities. The idea was not obviously incoherent. But economics is not about plausibility; it is about revealed preference. Consumers vote with their spending, not with their enthusiasm.

Transaction volumes on the marketplace collapsed as interest in NFTs faded. Revenues were negligible. The initiative was eventually wound down. Official explanations cited regulatory uncertainty, but regulation does not extinguish demand. When consumers value a product, they find ways to access it. In this case, the market delivered a negative verdict.

A later decision was even more revealing. In late 2023, GameStop authorized its CEO to invest corporate cash in publicly traded securities. This was not an operating strategy aimed at improving production, logistics, or customer experience. It was a financial strategy. At that point, the firm was no longer primarily engaged in entrepreneurial discovery through production and exchange. It was implicitly conceding that returns might be more reliably earned through asset markets than through serving customers. More recently, the decision was made to enter the collectibles business, with early signs of success as the primary business of selling games continues to deteriorate.

Stock price behavior reinforces this distinction between trading success and business success. GameStop’s post-squeeze history, even recently, has been characterized by extreme volatility. Investors who entered early and exited at precisely the right moment realized extraordinary gains. But those outcomes depended on timing, coordination, and tolerance for violent drawdowns — not on patient ownership of a firm generating rising cash flows. Over longer horizons, returns have been weak relative to risk. Holding the stock proved far less rewarding than trading it.

By contrast, firms operating in adjacent or overlapping spaces – such as Best Buy, Dick’s Sporting Goods, Chewy, or Take-Two Interactive – generated value through far more ordinary means: selling products people wanted, managing costs, and producing operating cash flow. Their returns lacked drama, but they displayed durability. A successful trade validates a market position under unusual conditions. It does not validate a business model.

What, then, was delayed by the short squeeze? Most importantly, the liquidation counterfactual. Absent extraordinary access to capital, GameStop would have faced binding constraints by late 2020 or early 2021. Management would have been forced to close stores more aggressively, sell assets, renegotiate leases, and concentrate narrowly on whatever segments could plausibly generate positive cash flow. Some capital would have been written off. Employees and physical locations would have been redeployed elsewhere in the economy. This would not have been painless, but it would have represented a rapid resolution of error.

Instead, that liquidation – which might have sent its assets into other, more competent hands – was postponed. Capital remained locked inside a firm whose entrepreneurial direction remained unclear. From an Austrian perspective, this is not a moral failure but a systemic one: the knowledge embedded in losses was not allowed to do its work. Discovery slowed. Misallocation persisted.

So did the short squeeze save GameStop, or did it merely preserve it? The honest answer is that it did both. It saved the firm financially while leaving its economic status unresolved. Survival was secured. Validation remains pending. Austrian economics cautions against mistaking one for the other.

Markets are powerful coordinating mechanisms, but they are not redemptive. They can rescue firms without validating them. They can delay liquidation without ensuring renewal. Ultimately, only consumers determine whether a business deserves to persist.

Until GameStop converts the time it purchased into durable, self-funding cash flows, its story remains an open question — not a triumph of markets, nor a failure of them, but a reminder of the difference between staying alive and being worth keeping.

Full empirical and methodological analysis can be found here: GameStop Five Years Later: Capital Market Intervention and Corporate Survival. SSRN: 6022957 (jump to PDF).

0 Comments