“Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after the orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself from being polluted by the world.” – James 1:27

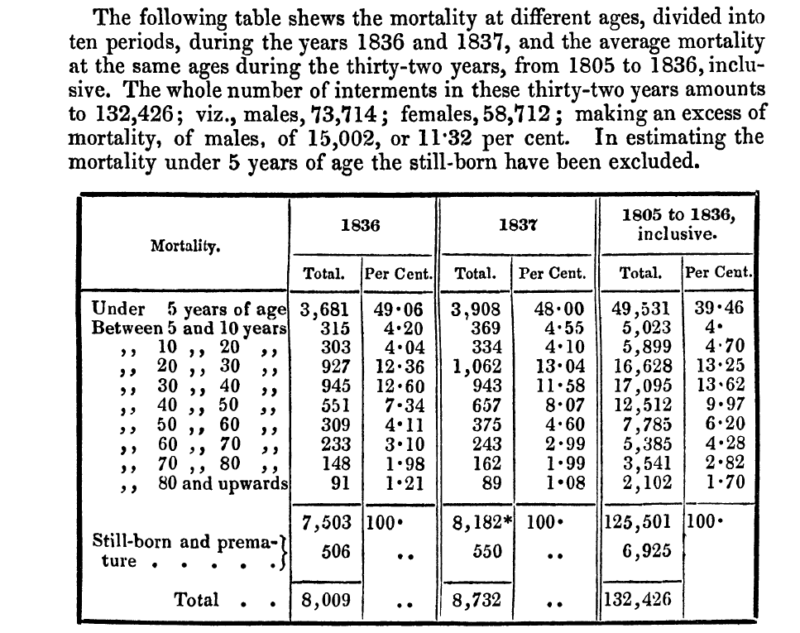

In 1836, the average life expectancy for a person living in New York City was only 25 years old. More alarmingly, of the 7,503 people who died in New York City that year, nearly half died before reaching their fifth birthday. Less than 10 percent of the deaths at that time occurred in individuals over fifty years old. This was largely due to the fact that mortality rates were so high in young people at that time.

Just as a comparison to understand how grim these statistics really are, let’s look at the mortality rates in the US in 2010. According to UNICEF, less than one percent of deaths in the US occurred in children under five years old; and, according to the CDC, nearly 45 percent of deaths occurred in individuals over 65. What this means is that, thanks to modern medicine, increased standards of living, etc., the US has seen an inversion of mortality rates from 184 years ago: today the majority of deaths occur in older people and only a small fraction of deaths occur in young children.

Unfortunately, low life expectancy was not the only social ill plaguing New York City in the beginning of the 19th century. In 70 years the population of New York City grew dramatically, from just over 33,000 people in 1790 to over 800,000 in 1860—a 24 fold increase. Technological advancements in transportation such as steamboats and railways brought people into contact with one another more frequently than ever before. That, coupled with poor water and air quality, meant that disease ran rampant through the streets of antebellum New York, especially in the densely populated areas inhabited by the poor. Low life expectancy meant that many men and women were left widowed and children orphaned.

City almshouses, remnants from the Colonial period (illustrated by figure 2), were not equipped to care for the growing number of poor, which often left them overcrowded, unsanitary, and breeding grounds for disease and abuse. By 1814, nearly 25 percent of the city’s population received some sort of charity or aid due to the economic distresses caused by the War of 1812.

After emigrating to New York City in 1789, Isabella Graham and her daughter Joanna Graham Bethune vowed to improve conditions for the city’s most vulnerable population: widows with young children. In 1797, Graham began to do just that. She founded the first women-run nonprofit corporation, the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children (SRPW). This charitable organization was unique in the fact that, prior to this point, women-run charities had been informal, neighborhood “sewing rings” run by affluent ladies. Never before had an American philanthropic institution been founded and operated solely by women, who were largely seen as being incapable of, and not possessing traits necessary to run a corporation. The SRPW was run by two “directresses,” a secretary, a treasurer, and twelve “managers,” whose duties were to screen each prospective widow in their assigned district and ensure their care, should they be accepted into the program. By 1821, the society estimated that it had aided over one thousand people annually (over 200 widows and nearly 900 children under 10 years old). By 1822, the society was just as, if not more, impactful than several other aid organizations run by men.

Isabella Graham founded the SRPW because she saw an unfulfilled need. At that time, the government allocated less than 0.3% of its GDP towards social programs, which, in conjunction with rapid population growth, meant that many people slipped through the cracks and did not receive the aid that they so desperately needed.

Graham kept overhead costs low and directed aid to those in need quickly. Donors saw that her organization efficiently met its laudable goals, so they preferred funding her instead of government or less focused charities. This exemplifies why private aid often works so much more effectively than public, government-sponsored aid. Because nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are smaller and not involved with the government, they do not have to go through the bureaucratic red tape that government agencies often face. Additionally, competition from other private-based aid organizations provides ample motivation for NGOs to keep administrative costs low.

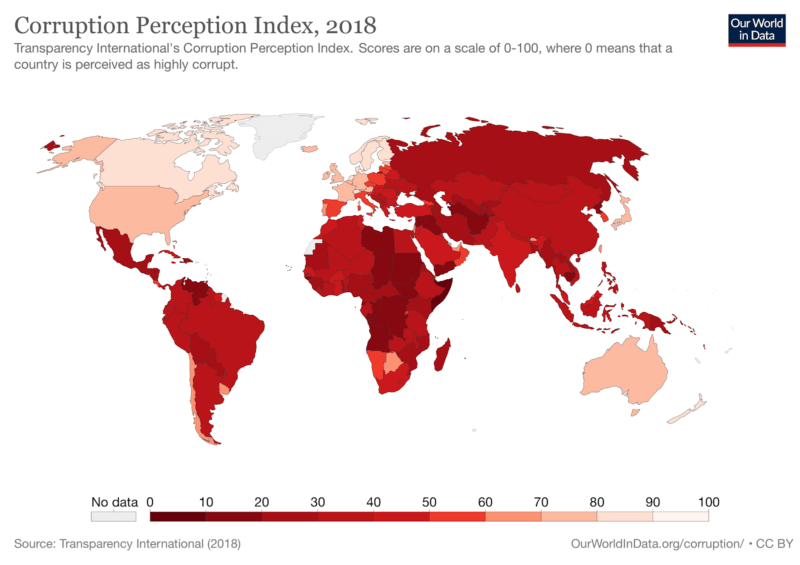

A similar situation arises today in the case of international donations. Official international aid (aid given by the government of state actors) is given to foreign governments for allocation. “Leakage” often occurs due to corruption and bribes, decreasing the amount of aid to reach people who need it. Consequently, foreign aid frequently strengthens the very tyrants who impoverished the masses in the first place, creating a cycle of poverty and aid. In Figure 3 and Figure 4, one can see that countries with high levels of poverty often have high levels of corruption, especially in Africa.

Government-sponsored aid, such as that provided by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, has higher chances of leakage because it generally goes through the public sector. Private aid, on the other hand, can be given directly to frontline workers who can allocate the aid accordingly. Examples of private aid include the Red Cross, Médecins Sans Frontières, Global Philanthropy Forum, and the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis, and Malaria.

Though private-based aid can often be allocated more efficiently than government-based aid, one should not make the mistake of generalizing all government-related aid as bad and NGO-related aid as good. Although a good portion of government aid is lost due to overhead costs and leakage, some of it does reach people who need it. While NGOs are generally perceived as more efficient in distributing aid, such claims are difficult to assess due to a lack of benchmarks and too much trust on the part of donors, as well as transparency challenges. Though charity organizations in countries like the US and UK have fairly strict reporting requirements, countries with less stable public infrastructure have more relaxed oversight, potentially leading to serious misallocation of donor funds. But, these measures of oversight cannot completely ward off sham charitable organizations, as Frank Brieaddy from the Charity Navigator, pointed out. Brieaddy says that over eight years Syracuse-based homeless shelter, Help the Needy, raised at least $5.5 million “without offering a public accounting of where the money went or gaining federal recognition as a legitimate nonprofit organization.”

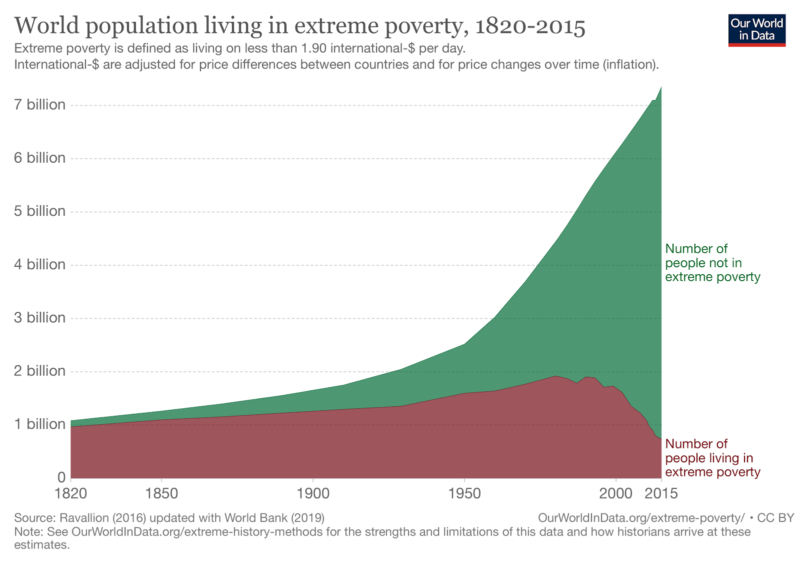

The bottom line is, aid has never been and will never be a lasting solution to poverty reduction. When used correctly, it can provide temporary relief for sudden changes of circumstance such as job loss or natural disaster—but that’s about it. The work of Isabella Graham and her daughter did much to alleviate the suffering of the widows and children within their care, but it did not provide any upward mobility to lift them out of poverty. This is because aid is like anesthesia: it temporarily lessens the sting of poverty but has no means to actually heal the source of infection. Only freedom can do that. In the 1950s, the percentage of people not living in poverty began to rise dramatically (as illustrated by Figure 5). This corresponds to a massive shift toward free markets and globalization also occurring during this time.

Though international aid should definitely not be considered a primary strategy toward poverty reduction, it still has an important role to play in lessening the side effects brought on by poverty, such as hunger and disease. We must continue to develop and correct the ways that we are allocating funds to those in need, so that it fills hungry mouths rather than lining politicians’ pockets.

0 Comments