Silicon is the crude oil of the Digital Age. Millions of metric tons are mined every year in China, Russia, Norway, the US and elsewhere, much of which is used in the $500 billion global market for semiconductors. In turn, the manufactured silicon chips, wafers, and integrated circuits power tens of trillions of dollars worth of hardware running personal and business software, wired and wireless communication devices, consumer electronics, automotive components, industrial technology, and other critical processes worldwide.

Manufacturing semiconductors involves not only a network of highly specialized firms in an often multistage production process, but a dependence upon firms which produce the ultra-high precision equipment for the fabrication procedure. Thus while silicon is a metalloid and accordingly a commodity, the various chips employing it describe a spectrum of complexity that runs from basic microcontrollers to high performance processors: each of which rarely has substitutes.

“It’s not rocket science—it’s much more difficult,” goes one of the industry’s inside jokes…Manufacturing a chip typically takes more than three months and involves giant factories, dust-free rooms, multi-million-dollar machines, molten tin and lasers. The end goal is to transform wafers of silicon—an element extracted from plain sand—into a network of billions of tiny switches called transistors that form the basis of the circuitry that will eventually give a phone, computer, car, washing machine or satellite crucial capabilities.

Beginning in 2020 and accelerating into 2021, a chip shortage has, to various extents, plagued the estimated 169 industries which depend upon them. While a small number of firms stockpiled chips in anticipation of just such an occurrence, the overwhelming majority of firms for which semiconductors are a key factor input have had to reduce their output. But like so much else, the inadequate supply of semiconductors is at the center of a handful of causes, with policy blunders front and center among them.

ICE FactSet Taiwan Core Semiconductor Price Return Index (2015 – present)

Neo-Mercantilist Beginnings

Two major policy actions of the Trump Administration laid the initial groundwork for the present paucity of chips. The first came in 2018, when

the United States imposed 25% tariffs on semiconductors imported from China. A core issue involved allegations that unfair trade practices by China hurt a variety of US-headquartered companies, including in the semiconductor industry. Tit-for-tat government actions resulted in new tariffs covering over $450 billion, or more than half, of bilateral trade between the two countries by the end of 2019[.]

That led to a 12% decline in global semiconductor revenue between 2018 and 2019. But shortly thereafter, a second and

arguably more economically destructive line of conflict for the industry began in 2019, with a series of US export controls targeting the global semiconductor supply chain. Initially, US policy was motivated by national security concerns. Limiting US semiconductor sales was aimed at keeping Huawei–a Chinese…Fortune global 500 company, whose 5G equipment the US government viewed as threatening critical network infrastructure–from accessing inputs it needed to manufacture base stations. The initial US export controls didn’t work: Huawei purchased semiconductors from companies in Taiwan and South Korea instead. The United States responded with new export controls and threatened to cut off the niche equipment and software provided by smaller American firms to those foreign companies if [they] did not stop selling to Huawei.

As lockdowns and indoor occupancy limits were imposed with the spread of Covid-19, many semiconductor manufacturing facilities came to be operated with skeleton crews at lower capacity. The already tariff-slowed pace of chip production began to decline more precipitously.

The Stimulative Factor

Only a few weeks into the widespread imposition of pandemic policies (lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, social distancing requirements, compulsory masking, and so on), the first stimulus checks were received by an estimated 162 million bank accounts, which contributed some portion of the total $271 billion to a consumptive binge. Several additional stimulus payments have been made since then, and on top of that the American Rescue Plan extended Federal unemployment bonuses through September 6th, 2021. Furthermore, under the Child Tax Credit revisions, the

Internal Revenue Service (IRS) will pay out $3,600 per year for each child up to five years old and $3,000 per year for each child ages six through 17. Starting July 15, monthly payments will be issued through December of 2021, with the remainder to be issued when the recipient files their 2021 taxes. The benefit will not depend on the recipient’s current tax burden. In other words, qualifying families will receive the full amount, regardless of how much — or little — they owe in taxes. Payments will start to phase out beyond a $75,000 annual income for individuals and beyond $150,000 for married couples. The more generous credit will apply only for 2021, though Biden has stated his interest in extending it through 2025.

Aside from the incredible folly of government policies which severely restrict the supply of demanded foreign goods via tariffs and, shortly thereafter, inundate under- and unemployed consumers with disposable income, fiscal redistribution has broadly and undeniably played a major role in exacerbating the shortages observed over the past sixteen months.

The Remote Access Crunch

As early as January 2020, a mass exodus of employees from offices to work-from-home status began, and with it a leap in demand for laptops and other business technology. Schools additionally closed nationwide, requiring many parents to acquire or upgrade home computers. A Harvard Business School study found that nearly 80% of large companies and 45% of small companies shifted to some measure of remote work last year, with 93% of households containing school-age kids involved in some form of remote learning. Another portion of the increase in demand owed to efforts to cope with boredom: semiconductor-driven smart televisions with digital streaming capacity, tablets, phones, and other entertainment technologies.

Over 302 million computers were purchased in 2020: a 13% increase over 2019 and the most since 2014. But there was a snag: the burst of demand struck not as it typically does–throughout the year, with anticipated increases in the late summer (with the start of the academic year) and after Thanksgiving (for holiday gifts)–but during March and April. And owing to this rush, the chip shortage began to worsen, with consumer goods prices rising. “A webcam that normally costs $50-$60 is now around $100, and a dock that should be about $180 is $320 on Amazon Prime” with many items rapidly going out of stock, as NBC News reported in April 2020.

In several jurisdictions, the sudden and profound spike in tech prices led to accusations of illegal price gouging. None, however, led to government legal action (charges or confiscation) as laptops, tablets, and other such products are not categorized as essential to helping check the spread of Covid-19. (Masks, hand sanitizer, disinfectants, and the like are subject to gouging penalties under the Defense Production Act of 1950, invoked by the Trump Administration on 18 March 2020.)

Game consoles such as Microsoft’s Xbox and the Sony PS5 (Playstation 5) began disappearing from store shelves and online retailer inventories as well. Already popular gifts, the prospects of longer lockdown periods (‘just two weeks,’ ad infinitum) made gaming systems particularly desirable goods. By Thanksgiving 2020, console prices were skyrocketing, with PS5s listed on certain auction sites for up to $2,000: several times the manufacturer’s suggested retail price.

Automotive Production & Sales

By mid-spring 2020, the full implications of the effect that shutdowns, stay-at-home orders, social distancing, and the like would have on many businesses became starkly apparent. As car dealerships reported cancelled appointments and entire days without a single walk-on, auto manufacturers began to cancel orders for new inventory. As expected, sales of new cars plummeted initially. But within several weeks, abetted by the introduction of 0% financing deals and a host of other incentives, plus being awash in stimulus funds, demand for new vehicles exploded. Both lot supply and production were caught flat-footed.

US Auto Sales Total Annualized SAAR (2010 – present)

Dealer lots quickly emptied of the supply of the most desirable makes and models of autos. Yet in many cases they failed to refill, as many vehicles in mid-production couldn’t be completed for want of chips to run battery management, driving assistance, connectivity, and numerous other functions pivotal to the automotive advances of the past twenty years. A profound representation of the production shortfall is seen in Ford’s massive stockpile of vehicles awaiting semiconductors at the Kentucky Speedway. The thousands and perhaps tens of thousands of vehicles amassed there, waiting for silicon chips, is allegedly visible from space.

Toyota, which owing to prescience or luck stockpiled semiconductor chips in advance, was able to produce and sell enough cars to soak up some of the sudden demand. It beat GM as the number one seller of cars in the US for the first time ever in the second quarter of 2021. Ford reported a 27% fall in June new vehicle sales from one year ago (2020 to 2021), and analysts have predicted that a currently estimated 477,000 planned but unproduced cars could number 1.1 million by the end of 2021.

As new cars disappeared from lots and weren’t replaced, the prices of used cars jumped. The May 2021 CPI indicates that used car prices have increased by roughly 30% on a year-over-year basis.

Fire and Water

In July 2020, the first of a number of ‘elemental’ intrigues further hurled wrenches into the gearworks of global semiconductor supply chains: a fire broke out at a Nittobo plant in Fukushima, Japan. With a pivotal role in producing fiberglass for printed circuit boards (PCBs) the damage from both fire and flame suppression caused output from that facility to fall by at least 20%. Three months later and eight hundred miles south of that, another fire erupted at the Nobeoka City Asahi Kasei Microdevices (AKM) semiconductor factory. After raging for three days, analysts described the conflagration as “creat[ing] supply chain interruptions for many end products[.]”

And in March of 2021 a conflagration at the Renesas Electronics building in Hitachinaka, Japan completely destroyed 17 chip manufacturing machines and the location’s “clean room.” The total damage at the time was estimated to take up to six months to recover from.

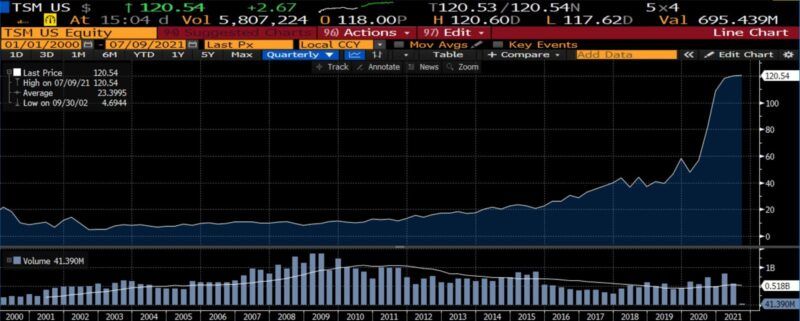

Taiwan Semiconductor ADR price (2000 – present)

Meanwhile, the uncommonly tranquil summer and fall of 2020 in the Pacific and Phillppine Sea, which typically features three or four typhoons annually, led to a drought in Taiwan. By some accounts, this is the nation’s worst drought since 1964. And this might not arouse much concern, except that Taiwan is the world’s foremost semiconductor foundry market, and manufacturing chips is a particularly water-intensive procedure.

Taiwan’s leading semiconductor producer and the world’s largest contract chipmaker, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Ltd. (TSMC)…uses more than 150,000 tons of water per day, [volumes] approximating 80 standard swimming pools…Due to the drought, TSMC and other semiconductor manufacturers have been depending on water trucks to maintain production. It is estimated that TSMC will spend over 23.69 Euro [around $28M] on the water trucks this year, exceeding its original budget planning. Global supply has been affected since…[and] microchips are likely to become rarer and rarer.

The impact of the water shortage has (as does much, today) led to opportunistic demagoguery. These include assertions that the unsung agent of Taiwan’s chip manufacturing problems is climate change, and calls for firms which depend heavily upon Taiwanese foundries (including Apple, Qualcomm, and Nvidia) to diversify their sources of supply.

As It Stands

Thumbing its nose at the Ricardian notion of comparative advantage, in July 2020

the United States Senate approved the FY2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which contains an amendment passed earlier this week, with little floor debate and by a 96-4 margin, that would provide billions of dollars in new federal support for the U.S. semiconductor industry, most notably tax credits and grants for the construction of new domestic manufacturing facilities. The House passed a similar bill with a similar amendment earlier this week, so the legislation now goes to conference, where the subsidies are expected to survive.

The purpose of the jingo-ensconced CHIPS (Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America) Act is to “[e]nsure [US] leadership in the future design, manufacturing, and assembly of cutting edge semiconductors…[a]s the Chinese Communist Party aims to dominate the entire semiconductor supply chain.” In May 2021 Congress was debating the form that such aid should take, and in June 2021 some decisions were reached.

Interventionism has, for time immemorial, generated unintended consequences. Nevertheless it is likely that social distancing and capacity restrictions in the early phases of the pandemic would have led to decreased semiconductor chip output anyway. But with respect to national security concerns, the age-old question regarding whether markets or government bureaucracies best accomplish such goals should be the initial conversation.

With respect to the silicon facet of the US-China trade war, the Peterson Institute for International Economics asks rhetorically:

Would a more rational US strategy have been to keep China ‘dependent’ on American semiconductors? Suppose US firms had been permitted to sell all except the most sophisticated chips, but the US government maintained its restrictions on sales to China of semiconductor manufacturing equipment and EDA [Electronic Design Automation] software. US semiconductor firms at least could have maintained the revenue and profits to continue to finance their own R&D without the need for federal subsidies. Without the foreign inputs, Chinese manufacturers would have been unable to upgrade to the smaller and faster chips at the technological frontier than many using industries demand.

From the consumer’s perspective, elevated tech prices due to ongoing shortages endure in many areas, and will linger for some months. As has been reported in technology, business, and trade publications, the price effects of the chip shortage are now beginning to manifest more broadly in personal computers. As of late June 2021,

prices of popular models of some laptop consumers have crept up over the past two months, among other electronics becoming expensive at retailers. A laptop geared toward videogamers–made by Taiwanese manufacturer ASUSTek Computer Inc.–that Amazon lists as its bestseller rose from $900 to $950 this month, according to Keepa, a site that tracks prices. The cost of a popular HP Inc. Chromebook rose to $250 from $220 at the beginning of June. HP has raised consumer PC prices by 8% and printer prices by more than 20% in a year.

Although one major retailer reported raising prices of goods with semiconductor-related components by 15% thus far in 2021, an executive commented, “[c]ertain components now cost as much as 40% more.” That even toasters now contain silicon chips is beginning to dawn on purchasers, in some part due to sticker shock.

Dollar Volume Growth Electronic Sales and Computer Software (2015 – present)

Back in the automobile markets, profoundly unusual price aberrations have materialized. Recently the received wisdom that a new car immediately and irretrievably loses a chunk of its value when its rear tires leave the lot has been overthrown – at least temporarily. Why?

[S]ome used cars and trucks are worth even more than they cost when they were new. What makes your Jeep Wrangler, Subaru Ascent, or Honda Civic worth more than it was when it was brand new a year ago is the simple fact that it exists. It is a car that has already been built at a time when there is enormous demand for cars and SUVs and not enough inventory to meet that demand [d]ue to disruptions in supplies of crucial computer chips.

Where traditionally a used car is priced on average 11% less than a comparable new car, that average has now narrowed to about 3%. And in several cases, used car prices eclipse those of new cars. As of last month a Kia Telluride sells for over 8% higher used than new. So too do GMC Sierras (over 6%), Toyota Tacomas (over 5%), and the Mercedes Benz G-Class (over 4%).

Other discomposing factors are lurking on the periphery, threatening to compound existing semiconductor insufficiencies. Owing to the so-called Delta variant of Covid-19, lockdowns at several major Chinese shipping facilities (Shenzhen, the third largest in the world, and Guangzhou, the fifth largest in the world) have resulted in waiting times for cargo ships to soar from twelve hours to sixteen days.

A highly technical discussion of how the dearth of chips may abate can be found here.

Inconclusive Conclusions

After carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and a handful of other elements upon which life itself is built, silicon has been a particularly impactful element in human innovation. Tremendous bounds in productivity, driven by incremental improvements in technology, have driven inexorably higher levels of prosperity. In exquisitely engineered configurations, it has made once inconceivable bounds in computation, data analysis and management, information transfer, and a wide panoply of other advances not only possible, but quotidian. Indeed, it is sinfully easy to overlook the incredible union of physics, engineering, and economics that semiconductors contemplate and conflate their ubiquity with simplicity.

Early in 2020, predicting that the spread of a respiratory virus would lead to a scarcity of inputs that constitute the very backbone of all modern technology would have sounded ludicrous. But amid a hotchpotch of non-pharmaceutical state interventions, geopolitical wrangling, income redistribution, sudden shifts in work patterns, and the knock-on effects of those, that has occurred and persists.

No one, and certainly not I, can accurately forecast when, where, or how the current array of price distortions and shortages will normalize. An appreciation of the sophistication of modern commerce requires recognizing the ease with which the commonplace can be derailed by seemingly innocuous policies. And relatedly, the tendency for secondary and tertiary effects of political miscalculation to unexpectedly bubble up in odd corners and folds of the economy.

0 Comments