In the Coronavirus crisis, large fiscal stimulus packages, which aim to kickstart growth, continue to push up public debt from already high levels. The sustainability of public debt in many industrialized countries is meanwhile strongly dependent on the government bond purchases of central banks. As growing debt levels seem to restrict the scale for new debt-financed expenditure programs, a discussion concerning debt write-offs has started. Argentina is an interesting case study. The rise of public debt in Argentina started in the mid-1970s (Figure 1). Since then, most debt has been public debt, with the government having found different ways of doing debt write-offs, yet without fundamentally solving the problem.

Figure 1: Total Public Debt of Argentina

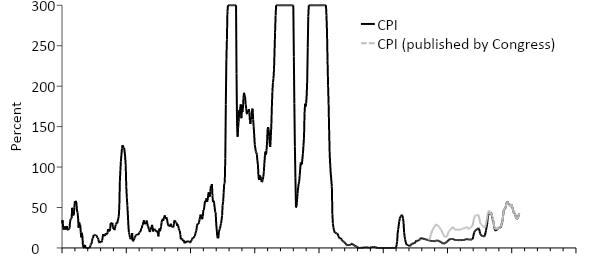

First, peso-denominated debt, which was for instance held by the private sector in Argentina and public social security institutions, was devalued via inflation. If the nominal value of government bonds is constant, it is devalued in real terms, when the price level rises. As the nominal GDP increases, debt as a percent of GDP declines. In Argentina, inflation particularly soared in 1975-1977, 1982-1986 and 1988-1991 (Figure 2). Yet, in anticipation of inflation most bonds became indexed to inflation or issued in foreign currency. By 2021 government debt of the Republic of Argentina stood at $335 billion, with 23.5% being denominated in pesos and 76.5% in foreign currency (mainly dollars).

Figure 2: Inflation in Argentina

During 2007-2015 there were political interventions in the INDEC to “underestimate” inflation. (With lower officially estimated inflation, interest rates on inflation indexed-bond are lower.) Therefore, an alternative inflation rate was published by the Congress, which was substantially above the official rate. See El Hub Económico (2021).

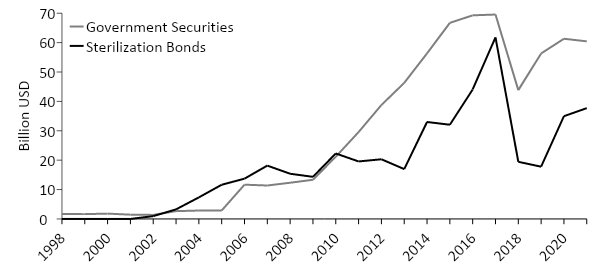

Second, the central bank of Argentina has acquired peso-denominated government bonds and T-bills, as a direct way to finance government peso expenditure. It also granted temporary advances in pesos to the government, of which the volume in the central bank balance sheet stood at $15.17 billion by March 2021. In addition, to acquire dollars the government has issued so-called Nontransferable Bills denominated in dollars, which the central bank swapped against the dollar reserves. By March 2021 the Central Bank of Argentina held Nontransferable Bills and other bonds from the National Treasury equivalent to $60.43 billion (Figure 3), which corresponds to 38% of total assets. The central bank is unlikely to reduce claims on the government – for instance by not revolving nontransferable dollar bills – as it is dependent on the government.

All claims to the government make up close to 50% of total central bank assets, with a substantial part being denominated in foreign currency. Because the acquisition of foreign reserves (for instance in case of foreign exchange intervention) and the build-up of claims on government by the central bank are financed via the expansion of the monetary base, they are ultimately financed by the private sector. The peso assets which are created by the acquisition of foreign reserves or government bonds – i.e. deposits of commercial banks at the central bank and currency in circulation – are devalued in real terms via inflation.

Figure 3: Central Bank of Argentina: Claims on Government and Outstanding Bonds

Third, capital inflows and the accumulation of government debt create inflationary pressure via monetary expansion. Central banks can contain this inflation by selling central bank bonds (Löffler, Schnabl and Schobert 2010) (in Argentina Lebacs or Leliqs). In March 2021, the outstanding amount of these bonds issued by the Central Bank of Argentina stood at $37.71 billion (sterilization bonds in Figure 3), equivalent to about 23% of total assets. To minimize the costs, often commercial banks are – more or less – forced to buy the bonds at interest rates below market rates, inter alia because sufficient alternative investment opportunities are missing. This gradual default forces commercial banks to shift the burdens to their customers, either in the form of rising lending or reduced deposit rates. With rising inflation, the real value of these central bank bonds declines.

Fourth, in Argentina the depreciation pressure on the domestic currency triggered by monetary expansion tends to be contained by outward-bound capital controls and foreign exchange restrictions (trabas). In practice, people have to provide genuine reasons for acquiring foreign exchange, with limits on foreign exchange purchases. Multiple exchange rates are a form of distributing the costs of inflation on different parts of the population, depending on the individual exchange rates to the dollar. In Argentina, dollars are mainly earned by the export-oriented farming sector. Foreign currency revenues have to be surrendered to the government with an export tax being applied (retenciones). The remaining returns are converted into pesos below at the (black) market rate. If farmers want to acquire dollars, for instance, to stabilize the value of their savings in the face of inflation, they have to purchase dollars at a worse dollar rate.

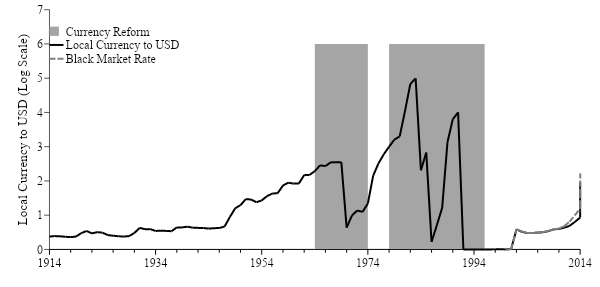

Fifth, dollar debt held in foreign countries by banks, households, international institutions or pension funds can neither be devalued by inflation nor by depreciation. The only solution for debt write-off is outright default, which occurred in the years 1982, 2001, (2014) and 2018/9. (See for instance Cachanosky and Thomas 2014). Usually, the process was catalyzed by a strong depreciation (Figure 4), which inflated dollar-denominated debt in terms of domestic currency, leading to default. This led into the restructuring of international debt, currency reform and the provision of international public credit, inter alia by the IMF. Today, the liabilities of Argentina at the IMF stand at $45 billion, and liabilities at all international public institutions at $77 billion.

Figure 4: Argentina: Local Currency to US Dollar

The upshot is that, over time, Argentina found different (overlapping) creative approaches to write off debt, which created the basis for the build-up of new debt, with distribution effects inside and outside the country. Domestically, the people holding cash and deposits at banks, and the farmers and the pension funds holding public debt can be seen as important groups suffering from the gradual default. From a wider perspective the financial repression imposed by the government and the central bank has depressed growth and therefore incomes. (See McKinnon 1973 on the negative growth effects of financial repression.)

Internationally, whereas some private vulture funds found brutal means to achieve full repayment on their assets, international public institutions such as the IMF were repeatedly willing to take over the risk. This leniency may be due to the fact that the international taxpayers seem unaware of the burdens. It has to be seen which strategies will be observed in the future in the industrialized countries.

We thank Nicolas Cachanosky for useful comments.

0 Comments