The Othering & Belonging Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, recently released a report, claiming that “Vermont, Alaska, and Maine were the three most effective states in responding to the coronavirus pandemic last year.”

Their assertion raises further questions, such as what does effectiveness mean and if it is comprehensive. Upon further investigation, we find that the study’s use of data and omission of multiple other factors prompts the need for more research and thorough analysis in order to make a generalized claim about effectiveness.

While the report does not explicitly state how they performed their calculations, the Institute provided the Covid-19 Index, ranking each state as follows:

The index incorporates three factors on the grounds that are “not in simple health or economic terms, but in terms of equity and inclusion:” Covid-19 infections (or cases), deaths, and tests performed. The data is useful for understanding outcomes of cases, deaths, and testing but misses many other important effects outside of the virus-related results, such as employment, business closures, crime rates, people’s mental health, and education outcomes.

In addition, the justification for each factor may be jumping too quickly to conclusions. The report suggests that a lower case per capita outcome reflects better policy and mitigation responses. Lower deaths per capita represents better healthcare infrastructure and smaller amounts of vulnerable populations. Finally, the level of testing measures “how robustly a country is trying to protect its people.” These explanations suggest a level of causation which is hard to account for based on just cases, deaths, and testing.

A Closer Look at the Data

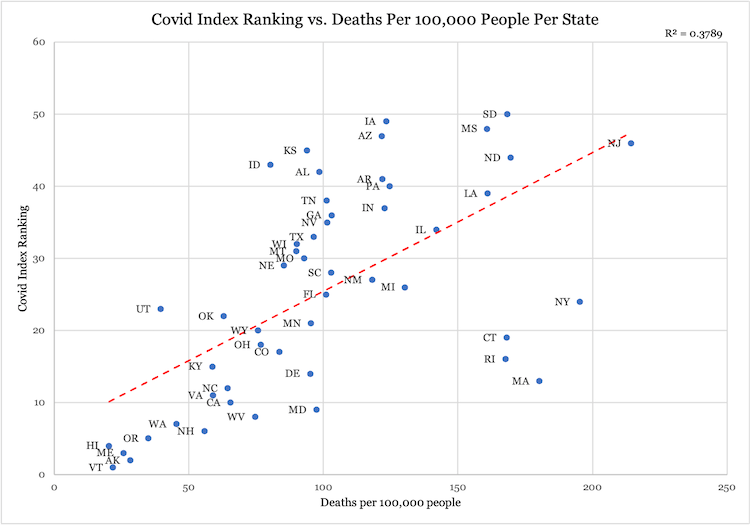

When we graphed the Covid-19 index against deaths per 100,000, we discovered that there is not a strong relationship. We mainly focus on deaths because it demonstrates the severity of the illness and quality of provided healthcare.

The graph shows that there is variation around the best fit trendline with many outlier states. The outlier states do not support one co-author’s claim that “the most effective states appeared to be those that carried out strong public health measures grounded in science.”

If effectiveness means low cases and deaths, then New Jersey, New York, and Massachusetts would score poorly. Yet, these states had some of the most stringent policies in the country but still experienced high case numbers and death rates. In addition, the report ranks Florida #25 and California #10 even though both states have similar outcomes in terms of cases and deaths.

The report explains that lower deaths occur in states with better healthcare infrastructure. However, we see the states with the most deaths – New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts – are ranked high for best healthcare according to U.S. News & World Report rankings (New Jersey #4, New York #7, and Massachusetts #2). Still, the Othering & Belonging Institute ranks New York #24 and Massachusetts #13 for Covid-19 response effectiveness despite the overwhelming evidence that their outcomes were undesirable. Meanwhile, Vermont, Alaska, and Maine – who have the best Covid-19 Index – are ranked worse for healthcare: #18, #22, and #26.

The report’s other explanation that lower deaths occurred in states with less vulnerable populations is also not supported. According to WalletHub, New Jersey, New York, and Massachusetts contain relatively smaller levels of a Covid-vulnerable population (NJ ranked #40, NY #27, and MA #48). Still, they have the largest death counts. On the other hand, Vermont, Alaska, and Maine are positioned at #47, #35, #22 for Covid vulnerability, thus having slightly more vulnerable populations but less deaths.

Since their explanations for death outcomes are contestable, there are other factors worth considering that could influence death numbers: population density, access to healthcare, levels of poverty, proportion of elderly population, nursing home population, level of preexisting health conditions, and number of multigenerational homes, and the list continues. The report even admits to these factors – not related to policy – as disproportionately impacting certain groups, for example:

African Americans were particularly vulnerable to the virus: they had less access to health care, had higher incidence of underlying risk factors like hypertension and diabetes, and were more likely to work in public-facing jobs with greater exposure to the virus. Additionally, the virus swept through larger metropolitan areas first and fastest, where African Americans disproportionately resided.

Important Outcomes Unconsidered

Although infection rates, deaths, and testing are easily quantifiable metrics, they do not fully illustrate what constitutes a good Covid-19 response. The Lowy Institute in Australia produced a similar comparison that even disaggregates performance into interesting categories, including regions of the world and different forms of government. As interesting as this information may be, it – like the Othering & Belonging Institute’s report – functions more so as a basic scorecard for cases, deaths, and testing rather than as an appropriate arbiter on the effectiveness of a policy response.

The first important metric that is often left out of both rankings is economic performance. To many, the pandemic response appears to be a pitting of the economy and public health against each other. However, this thinking fails to understand that there could be a balance between these two objectives through weighing the costs and benefits. Economic turmoil is a salient crisis in and of itself, but large economic shocks have also been correlated with long-term increases in excess death.

Furthermore, economic retraction in developing countries leads to an extensive list of issues, including widespread increases in food insecurity, which is directly related to adverse health effects in the short and long run. Lockdowns prompted extreme and unprecedented economic damage, seen as one of the sharpest economic declines in US history and around the world. By neglecting to account for economic damage in a response ranking system, we risk endorsing policies that may not only be ineffective but create a new crisis alongside the existing problem.

Additionally, the ranking criteria fail to account for the sociological damage various policies create. Closing down businesses, large events, and schools led to devastating mental health outcomes, particularly among young people. Endorsing or failing to discourage the serious social damage of public health interventions hinders our ability to make real cost-benefit analyses. Although the Othering and Belonging Institute mentioned the economic and social damage of pandemic policies in their report, these important factors were not incorporated in their ranking system.

Finally, there are institutional concerns with the way certain policy frameworks interact with abstract concepts like the rule of law, political stability, and the legitimacy of government institutions. AIER covered some of the serious questions regarding lockdown policies, the rule of law, and the ultimate foundations of our liberal democracy. Severe interventionist and arbitrary policy responses pose a serious risk not only to the constitutional frameworks of liberal democracy but to the legitimacy of public institutions.

Factoring In The Importance of Vulnerable Populations

Despite the report’s omission of several indicators of effectiveness in the actual index, the authors discuss who has been disproportionately affected and offer important explanations. However, as important as these explanations are, they unfortunately were not used in measuring the effectiveness of policy responses. The only factors considered in the Institute’s index as well as a number of others produced by different organizations are superficial measurements such as cases and deaths. The report makes a clear note about the importance of age when defining vulnerable populations. It notes that,

Age appeared to be a significant factor in risk of hospitalization or death from infection. More than 80 percent of the deaths in the United States occurred in populations sixty-five years of age or older, and just 2.5 percent of deaths among people forty-five years of age or younger.

Given this information, the Index could also factor in how well a policy response makes efforts to shield the elderly. On the flip side, it would also be appropriate to understand that differences in deaths per capita may be related to outbreaks among elderly populations and not necessarily the policy response as a whole.

For example, this may help explain Florida’s superior performance in preventing deaths compared to New York state. Florida made efforts to protect the elderly whereas New York sent Covid patients into nursing homes. At one point around 40 percent of all Covid deaths in the country were attributed to nursing homes despite comprising less than 1 percent of the population. In Sweden, Reuters reported that around 50 percent of Covid deaths were from nursing homes following a drastic failure to provide adequate protection. In this case, maybe Sweden’s lack of a lockdown was not the problem but the lack of oversight on nursing homes was.

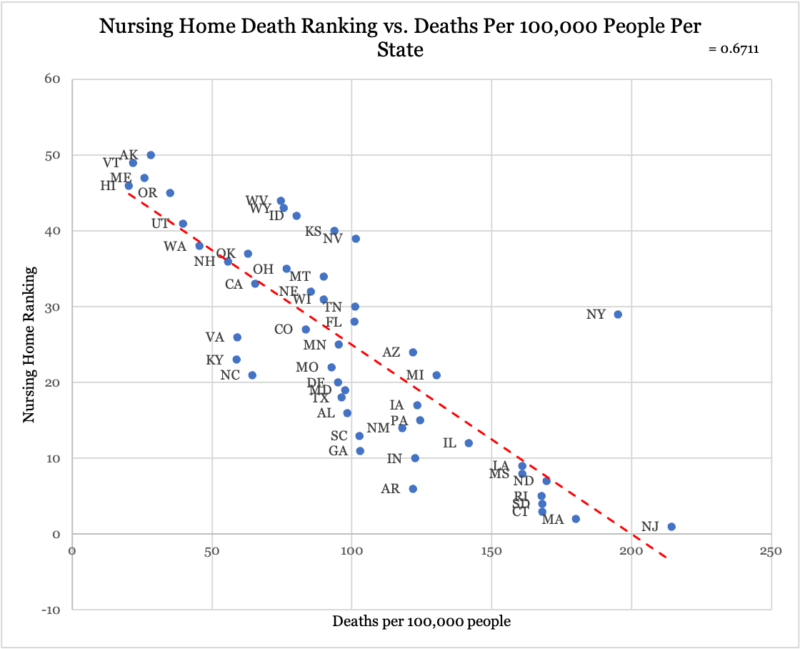

When looking at the nursing home rankings – based on percentage of nursing home population lost to covid-19 (with #1 being the largest percentage) – nursing homes deaths appear to play a larger role in outcomes. There is a stronger relationship when nursing home rankings are graphed against deaths per 100,000 people (Graph 1) than compared to the Covid-19 Index rankings provided by the Othering and Belonging Institute (Graph 2).

Graph 1

Graph 2

With this in mind, perhaps a good measure of a policy response is not necessarily based on broader deaths and cases, or stringency and testing, but how well nursing homes were protected. This would allow policymakers to better understand what policies are actually connected to preventing death and what is simply correlation with no causation, or in this case little correlation at all.

The report contains another insightful observation when it says,

The California Department of Public Health reported that Latinos accounted for more than 60 percent of deaths attributed to COVID-19, but less than 45 percent of the statewide population. In Los Angeles as well as San Jose, crowding and multigenerational households appeared to contribute to the lethality of the virus, especially among Latino and Black households.

This statement further demonstrates that the Institute understands the importance of protecting vulnerable populations, but the nuance is not captured in the policy response ranking. Acknowledging how disparate lifestyles linked to socioeconomic status lead to better or adverse consequences regarding Covid-19 is essential in evaluating the efficacy of public health interventions. This discernment can explain how outbreaks and deaths in certain areas may not be linked to the general policies implemented by the state, but the specific demographics of the population. Unfortunately, these important distinctions are left out of the Institute’s ranking system which only measures the broad categories of overall cases, deaths, and testing.

Although the report likely omitted these important factors to avoid complicating the ranking system, these intricate details are necessary for comparing policy effectiveness. In fact, without considering these nuances, we risk writing an incorrect narrative about policies.

Key Takeaways

Our analysis of the Othering and Belonging Institute’s report reveals a few key lessons. One is that many factors influence the death and case numbers and are not limited to those – policy responses, mitigation efforts, healthcare infrastructure, and level of population vulnerability – suggested by the Institute.

The Covid-19 index is not comprehensive and fails to consider nursing homes, multigenerational communities, access to healthcare, and more. Factors that are endogenous to the community rather than external factors (such as a policy response) may play a larger role than the Institute would suggest. In addition, outcomes should not just be limited to cases, deaths, and testing, but the economic outcomes, especially on a granular level.

In a court of law, the burden of proof falls on those who wish to take away the liberty of the accused. Likewise, in the realm of policy, the burden of proof should be on those who wish to impose laws and restrictions on an otherwise free population. This practice is not only morally sound but practically sound as well. Public health interventions ought to be justified through rigorous cost-benefit analysis and honest conversations about the limitations of the policies involved.

In the age of Covid-19, people understandably want quick answers and assurance about what their governments are doing right and wrong, which is what the Othering and Belonging Institute provides. Oftentimes, evaluations are far too superficial and do not account for important tradeoffs such as collateral damage whether economic, social, or physical. They also fail to encapsulate successes and failures to protect vulnerable populations, maintain public confidence, and account for specific contexts.

Given the abundance of confounding variables and omitted considerations, such broad comparisons tend to function more so as political Rorschach tests than sound indicators of policy efficacy.

0 Comments